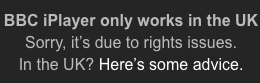

The featured image is a screen shot from the Netflix documentary “Amanda Knox.” The subtitle is her speaking, and that is the back of her head. Her rhetorical question comes in the last 10 minutes of the film.

Before she was finally exonerated in 2015, Amanda spent almost 4 years in jail for being convicted of murder. The documentary shows that her supposed culpability wasn’t scrutinized nearly as much as the sexy details of stories that marked the covers of countless newspapers and periodicals. Her blameworthiness was an illusion marked by fear: “It’s people projecting their fears,” she says offscreen. “They want the reassurance they know who the bad people are and it’s not them.” She’s sitting again in front of the camera, looking down to one side. “So maybe that’s what it is. We’re all afraid. And fear makes people crazy.” She looks up to the camera and offers a smile that’s like a shrug.

In a New York Times article about the impact the content of the debates, rallies, and subsequent memes from this election has on one 7th grade social studies teacher and his class in Wisconsin, the author, Julie Bosman, highlights the teacher’s struggle to teach this 2016 campaign: “Mr. Wathke has spent down time on evenings and weekends worrying about the effect of the campaign on his seventh graders….His students said they have also wondered what they were allowed to say about the campaign in class.” The students end up “sticking to the issues” during their mock debate, avoiding the kind of language and phraseology that could, as one student puts it, send someone to the principal’s office, or worse, get one expelled.

School is a controlled environment, and as we read the article we get the sense that Mr. Wathke is doing a good job maintaining it, despite the ever-looming threat of social media. Bosman knows this, and says:

We don’t know, either, how much kids absorb on social media. It may not be as much as we fear, but the content itself is not the main issue. If it were, that’s like assuming a child will never hear the word “fuck” so long as mommy and daddy never use it in the house. The word “fuck” is not a problem. The rampant use of it as entertainment could be. Bosman closes:

If the medium is the message, then it’s not the content that threatens these neutral yet impressionable minds, but the insipid pervasiveness of the content, i.e. social media, that generates popular vote. In “Amanda Knox,” when Amanda is looking at all the magazine covers that sensationalize or exploit, she is looking at the vote. When a child scrolls through an endless feed of memes, that is a vote. Perhaps it’s not the content so much as the availability and accessibility of it that worries Mr. Wathke and boggles Amanda Knox. Although, they are both humanitarian. Amanda, according to the documentary, advocates for the wrongly convicted. And Mr. Wathke, as a teacher, is perhaps the second most influential person to a child, next to a loving parent.

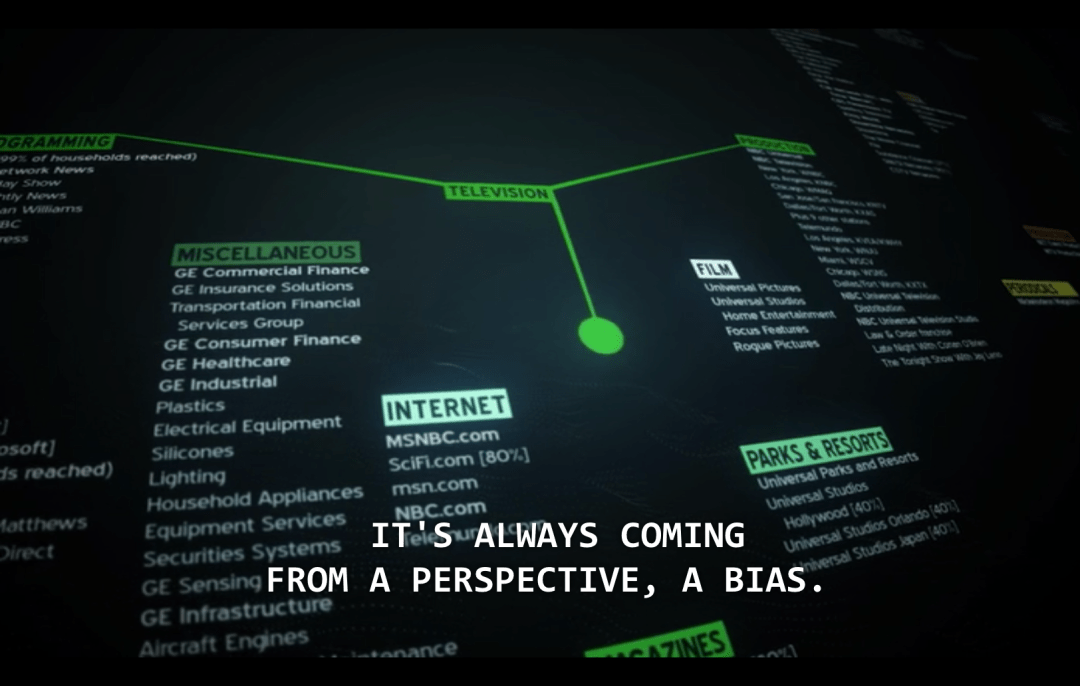

We are responsible for how much we partake in the medium, whether it be television, newspaper or magazine; how much we choose to engage; and whether or not we will populate our minds with the popular opinion, whatever it may be that day, or minute.